Can art change the world?

Before starting my fellowship, I so desperately wanted to believe that the answer to this question was yes. I knew, though, that if I traveled the world in search of answers matching my own, that I couldn’t call it “research.” For my grant, I’ve been specifically focused on art’s ability to change our minds about climate change and inspire environmental action. In the past four months, I’ve asked over sixty people on three continents this question and have received all kinds of answers. There are the emphatic “yes” responses, like Felipe from Rapa Nui who said, “Art is essential [to creating change].” Of course, there are also those who disagree. In the five sections below, you’ll hear from both sides.

Education

To learn more about Pedro’s fungi creations check out my artist series here

“Yes, art can educate people,” they say. But what does that actually look like? As Zambia art historian, Dr. Andrew Mulenga says, “Art can influence environmental issues in small ways if done continuously.” It can show us things that we weren’t aware of before.

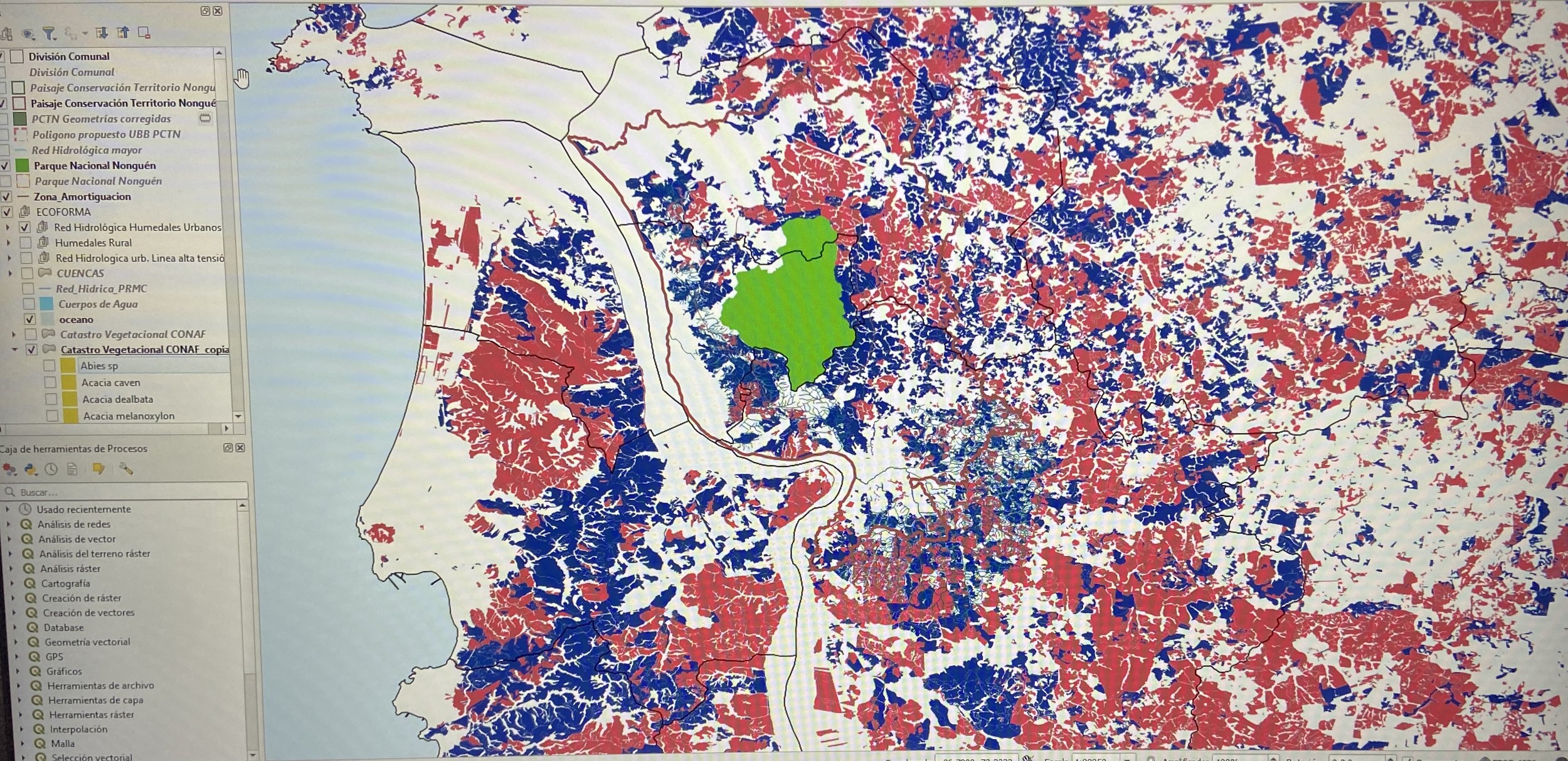

Red = pine tree monoculture forests | Blue = eucalyptus monocultures

The green zone is the Nonguén National Park.

When I’ve asked this question, many people have spoken about art’s ability to transcend languages and academic disciplines. Some have mentioned art’s ability to tackle complex problems because artists can often look at issues from multiple angles. As Chilean fungi artist, Pedro of Taller Percán, says, “Art is essential for visualizing problems completely.” Take maps for example. We use them often to help us understand complex issues. You might not consider maps to be art, but why can’t they be? When I visited Oscar Carrillo in Concepción, Chile, he had been creating maps to show the monoculture industry’s grip on Chile. Without those visuals, the data had just been numbers. Seeing the map of Chile colored red and blue all over told a different story. Some artists, like Marissa Solomon Shandell, also use art to make research accessible. Shandell simplifies complex studies into illustrations which she shares on her instagram.

Weeks earlier, while on our way to the LCOY climate change conference in Valparaiso, Chile, my friend, Genn and I paused to marvel at the most striking mural that I had ever seen. Samir’s mural is a haunting image about the avocado industry in the Petorca region of Chile. Everywhere I went, people were talking about Chile’s monoculture industries (namely: eucalyptus, pine, avocado and salmon). Another art collective, Agencia de Borde created an exhibit about the complexities of the eucalyptus monoculture industry by talking “about the relation between the eucalyptus/monoculture and the forest from the moods of coexistence between humans and no-humans perspective.” Murals, installations and maps are very different forms of art, yet each of these focused on Chile’s monoculture industry, an issue that I had known nothing of before arriving.

The most compelling example of art as an educational tool that I have encountered thus far would be SEKA (Sensitization and Education through Kunda Arts). I spent several days with this performance group in Mfuwe, Zambia, learning about their organization and watching them perform. Since 2000, SEKA has performed educational and entertaining skits about climate change, anti litter, HIV/AIDS, deforestation, COVID-19 and biodiversity, among others. They perform the majority of their skits in rural villages and often include audience participation. After performing their HIV/AIDs skits around the country, they noticed that people had taken their teachings to heart. SEKA decided that it was time to tackle a different issue. When I chatted with Pam Guhrs-Carr, a lifelong Zambian painter and sculptor about the role of art in environmental education, she admitted that she didn’t really see how her work could create change. “Performances like SEKA are more didactic,” she said.

There are those, like wildlife photographer, Edward Selfe, who aren’t so convinced that their art is having an impact. “I can definitely see the way that a wildlife photographer could and should have an impact from the point of raising awareness of the plight of wildlife and raising the profile of endangered species in unknown areas. To be honest, I’m pretty disappointed by the lack of impact we apparently have.” Edward and I agreed that wildlife photography likely had a larger impact when there were fewer photographers. “Everybody knows that rhinos, particularly in South Africa, are being lost at a rate of 2 or 3 a day. How many images of a half dead bleeding rhino does anyone need to see before they do something about it? As much as I would like to think that my work is a conservation platform, it doesn’t seem to make any difference to what’s going on on the ground.” Where Ed hopes that he can make a difference is in using his photos and social media following to bring tourists to areas that they wouldn’t have otherwise visited. “It’s all about money in the end - if you can channel funding into areas that weren’t going to normally get it, then I think that has a conservation impact much more than posting on social media and getting 50 likes.” Talking with Edward was simultaneously inspiring and heartbreaking, and his words have echoed in my mind since. He’s not alone in his thinking, though. When I spoke to New Zealand activist and creator Angela Winter Means of Greatest Friend, she also didn’t see how art as an education tool could create change. “I don’t think that you can change anything by sending a message out anymore. We are too saturated and disillusioned.” These two had said what most artists wouldn't. If we are already saturated with information, can art do anything more than be an educational tool? I wondered. I would find an answer on the most remote island in the world, Rapa Nui.

Promoting Clean-ups

Kassandra and her micro-plastic moai!

During my five days in Rapa Nui (aka Easter Island), I met several artists, including Kassandra, who make moai sculptures from micro plastics collected along the island’s beaches. This type of art makes a change by merely existing because it requires someone to first collect the trash. It also educates the viewer about the issue of plastic pollution in Rapa Nui and (hopefully) provides an income for the local artists. While I was there, I had made plans to do a beach cleanup with environmental activist and musician, Antu Tpano, but when we went to the beaches we couldn’t find any trash. A wonderful problem to have, I thought.

Frederick Phiri holding his nearly finished Guineafowl made from recycled metal

Across the world, another artist also turns trash into art. Frederick Phiri, a 22 year-old recycled metal sculptor in Mfuwe, Zambia has found that people “don’t see the beauty of waste materials.” Phiri says, “This art that I am doing is not just art. It also creates a sustainable environment for plants to regerminate….Where there is metal on the ground, there is zero chance for a seed to germinate. When I take [the metal], I create art and clean the environment so that plants can grow.” Now, whenever the safari lodges have scrap metal, they know to bring it to Frederick.

This type of repurposing “trash” materials was quite common in Zambia and South Africa, as traditional art materials are expensive and hard to come by, and recycling hasn’t reached most rural areas. In Mfuwe, I encountered several artists making sculptures and jewelry from poaching wire, watercolor paper from banana leaves or tea bags, sculptures from coffee pods, building bricks from plastic bottles and even animal sculptures from recycled paper. One of my favorite visits was with Niven and Mwamba from The Recycling Workshop branch of Tribal Textiles. For the past four years, they have been turning glass bottles into beads, chandeliers, charcuterie boards and tiles. Like Frederick, they now receive boxes of bottles from the lodges which helps to keep glass out of the landfill.

Providing Income

Another way that art can hopefully change the world is by providing a source of income. In most of Zambia, poaching is a big issue due to poverty and a shortage of jobs. It’s not enough to tell people not to kill animals without first offering an alternative. Some Zambian conservation-based organizations such as Tribal Textiles, Project Luangwa, Sishemo Beads and Mulberry Mongoose combat this by teaching locals to sew, weld or create art. Tribal Textiles, known for their hand-painted cotton fabrics, is the largest employer in Mfuwe with nearly 100 Zambians working at their shop, office and workshop. Tribal Textiles and Project Luangwa also help local artisans reach an international audience by featuring their crafts online and in stores. These organizations aim to provide the locals with more economic security, thereby decreasing the need for poaching.

Healing

Niven at the Glass Recycling Workshop

Why do people make art? Sometimes, we create to learn, investigate or process issues. Niven from the Glass Recycling Workshop in Zambia says, “Yes art can change our minds. We are learning a lot of things from the art that we are doing. I find sometimes that something that we didn’t know then, but through the art that we are doing we are able to know.” Funnily enough, most of the time when I would ask Zambian artists if they thought that art could change the world, they spoke about how it impacted them. When I first heard this, I was disappointed. They don’t understand the question, I thought. I was so focused on what art can do for others, that I hadn’t considered the role it plays for the artists themselves.

This was likely because I hadn’t ever reflected on why I make art in the first place. Often I am most compelled to draw when my internal world feels too overwhelming. As New Zealand activist and creator Angela Winter Means says, “Art could change the world if it is just people doing it for themselves, for their mental health.”

Community

Female-run art collective, Baobab Craft Shop, in Mfuwe, Zambia is a great example of women coming together to create environmentally conscious art.

I’ve also noticed that when I’ve shared my more personal art with others, it has resonated with some. The reality is that most of us who care about the environment experience some degree of climate anxiety. Perhaps art that addresses these challenges can help us to connect and realize that we aren’t alone. I’ve personally experienced this with the instagram art of @theofficialsadghostclub. While their work is more mental health focused, it appeals to over 611,000 people for its relatable illustrations, uplifting messages and honesty.

Frederick Phiri has seen art’s impact on our emotions firsthand with his recycled metal sculptures. “Art can definitely change people’s minds because you can feel sad but the moment you just look at the sculpture, then at least a smile will come up,” he says. “As we are interacting, art can motivate and inspire you.” Several artists that I spoke with also mentioned the power of art to create community. This can happen through the act of making art (ie. murals, exhibits, art collaborations, crafts etc.) and through seeing the art. Even in museums, art can start dialogues, spark curiosity and bring people together around complex issues.

Inspiring future possibilities

In Zambia, many people mentioned that the mere existence of art was inspirational. Sculpture artist Godbish Njovu had been creating work outside when he noticed children gathering to watch him. “They’d never seen art before,” he says. The children were curious and eager to help. Soon, Godbish partnered with Pam Guhrs Carr and they founded Conservation Through Art, a program using art to help children learn about and appreciate the wildlife in their backyard. Godbish now runs weekly classes with students, helping them make everything from “litter bird” sculptures to portraits out of plastic to a giant elephant made from cans and bottles. Both Godbish and Pam believe that teaching art can give their students technical skills, change their relationship to local wildlife and provide a source of income.

Art can also help us imagine new futures. New Zealand weaver, Michelle Mayn says, “Art can open up a new way of thinking.” Michelle also spoke about how arts’ often non-confrontational approach can cause people to be more receptive to new ideas. Similarly, Chilean documentary filmmaker Jose De La Parra spoke about how “art is a cultural practice to increase our plasticity and entropy in a good way. It can help us think on another scale.”

Many inventors have been inspired by science fiction TV, books or art. Whereas educational art tends to focus on environmental issues or problems, this type of art is usually more hopeful. Imagining better futures can give us a direction to move towards.

So, can art change the world?

Simply put, yes, but much depends on the scale and scope that you look at. Furthermore, “change” is very difficult to measure. It could happen overnight, over decades, or not at all. Often, we won’t know if our artwork has an impact unless someone chooses to tell us.

Since I started writing this a month ago, my findings have evolved as I’ve met more artists, activists and scientists. In the eight more months of my fellowship, I will travel to Taiwan, Turkey, Germany and the UK. I’m sure that those experiences will add more depth and clarity to this research, and that there are likely other ways that art can change the world which I have not yet encountered. Perhaps the answer lies in what Italian artist Theresa said to me as we drove through the Atacama desert: “Art isn’t special. Everything can change the world.” Art might just be one way to help us understand and connect to environmental issues. It’s not the cure-all that we need but it has the potential to create small changes, bring people together, educate, provide income, inspire and help us heal. And for me, that is enough.

What do you think? I’d love to hear your thoughts on this question and on the article in general. Please submit your response here , and feel free to reach out to me at www.amyspencerharff.com.